“When impossible love becomes possible” – how Temple Works and the British Library may finally have found each other

July 08, 2020

The greatest love stories aren’t always about young love. We are all ships that pass in the night and life is a series of sliding doors moments. Some of the strongest and most perfect bonds are formed late in life; making up for years of separation that might be tinged with regret, but are a necessary chapter in the story and make for a flawless ending and a yearned-for outcome that you savour all the more.

Partnerships and wholesome unions are formed in all walks of life. And if you can translate the power of love and fate to things such as buildings and institutions – and I think we can – then a quite remarkable revelation has recently been unearthed to suggest that the widely-anticipated potential alliance of Temple Works in Leeds with the British Library may be ‘meant to be’, and will provide a Hollywood finale that could now close the book on an unrequited love that has lay open for over a century and a half.

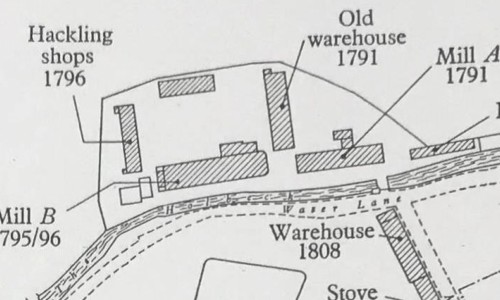

This achingly protracted affair of the heart might have remained a clandestine secret to the outside world, had it not been for the forensic research undertaken by Stephen Levrant Heritage Architecture (SLHA), the Conservation Architects appointed by CEG, and who provided the historical research in 2018 to establish a micro-level understanding of the design, construction and narrative behind the Egyptian palace in Holbeck, Leeds. Making the design curiosity a little less curious has been a painstaking undertaking for SLHA, with never-seen-before detail and documentation unearthed to put some flesh on the bones of the fascinating story behind this fascinating building.

And when you start on such a journey, there isn’t really an end. It is no surprise that trying to fully comprehend such a preposterous concept as Temple Works can take up every waking hour of your life, and that was the case for Lee Hutchings – Senior Historic Building Consultant at SLHA – who over Christmas and New Year 2019/20 made a quite remarkable discovery, which joins dots that no one previously expected to be on the same page.

“Well it actually came right at the end of all the research that we’d already done,” Lee begins in explaining the background to his discovery “and we’d gone through months and months and months of archive research and looking at anything online, any historic books that had been published, newspaper articles. And I’m the sort of person where, I’m a bit like a dog with a bone, and I knew there was something else, but I didn’t know what it was. I thought ‘there’s got to be something out there that tells us a little bit more’. So after all this research you get into the habit of using different iterations of words in your online searches. I can’t remember what it was that I typed because there’s been so many, but it just popped up.”

What popped up was a Pandora’s Box of breakthrough sleuthing that shows evidence of a link between the Marshall family’s Temple Works citadel and the British Library, going back to 1848.

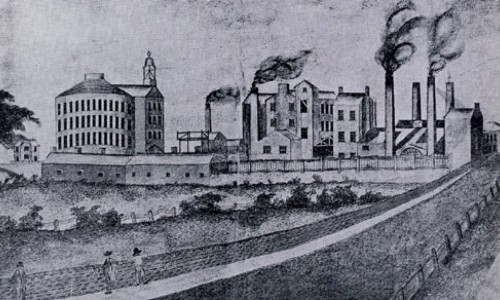

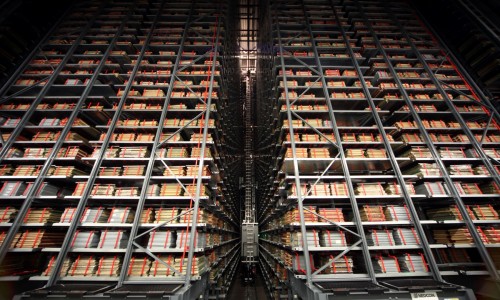

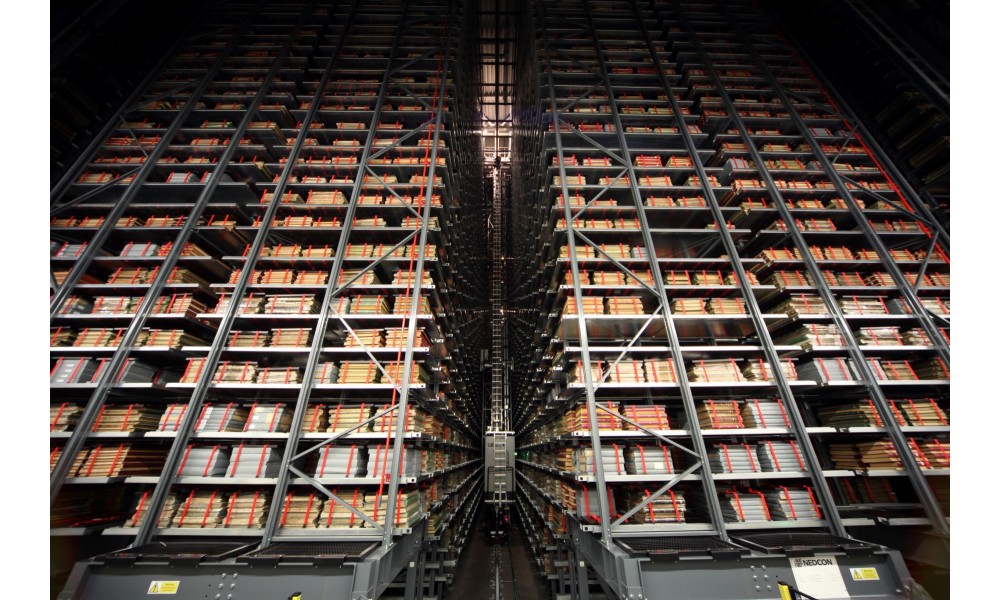

The British Library houses the biggest research collection in the world; a dizzying resource of books, manuscripts, journals, newspapers, magazines, sound and music recordings, videos, play-scripts, patents, databases, maps, stamps, prints and drawings. Hosting a 170 million-strong collection in both print and digital formats and across many different languages, it outgrew its original location inside the British Museum in the Bloomsbury area of central London, and with its iconic ‘Reading Room’, and has been housed at St Pancras since 1997. In addition, the 44-acre campus of document supply, reading room and long-term storage and retrieval at Boston Spa near Wetherby has been part of the Leeds story for nearly 60 years, and now holds over two thirds of the British Library collection. With the heritage grant as part of the West Yorkshire Devolution Deal, announced in March 2020, and Leeds City Council’s and CEG’s support, there is now real potential for a city centre British Library North to be housed in Temple Works, with James Marshall’s Egyptian edifice under consideration as a community fortress for learning, culture and innovation. The two-acre roof-lit mill hall, constructed in the nineteenth century as a mysterious but forbidding bastion against industrial espionage in the flax trade, in the twenty first century could become a digital-first access-to-all resource which is thrown wide open for the community and visitors to enjoy.

(Image source: Tony Antoniou/British Library - used with permission - an aerial view of the British Library at St Pancras in London)

(Image source: British Library - used with permission - an aerial view of the British Library at Boston Spa)

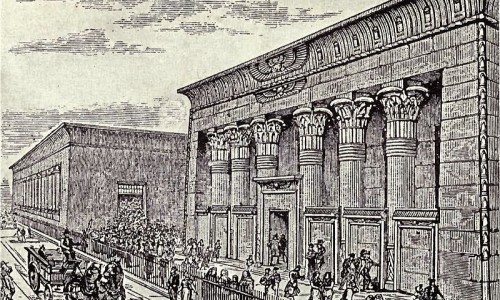

In 1823, Robert Smirke was the designer charged with the construction of a new British Museum, which has sat on the same site in London since 1753 in what was originally a 17th century mansion called Montagu House. King George ll gave a royal ascent to form a British Museum which would hold a collection of natural history, art and culture to reflect the expanding British colonisation, and hence extra wings and galleries were added over the years. Smirke was a neo-classical architect and he was responsible for the biggest re-build project, which started in 1825 and much of which is still in place today. For the 25-year span of its construction the re-build was dubbed ‘the largest building site in Europe’ and the result was the huge quadrangular British Museum that has become a recognisable feature of central London and Britain’s influence on the world’s historic culture ever since.

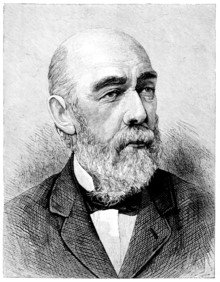

However, Smirke’s design didn’t sit well with everyone. James Fergusson was a Scottish architect, architectural historian and author who lived between 1808 and 1886. He was originally a businessman who used this pragmatic knowledge in his later studies of buildings and decorative schemes, for which he wasn’t formally trained but earned himself some credible industry recognition. Fergusson was in equal parts prolific and vitriolic, and didn’t hold back in putting his personal views down on paper. This included a 92-page pamphlet titled: “Observations on the British Museum, National Gallery and National Record Office, with Suggestions for their improvement”, and it was this pamphlet which Lee Hutchings came across in a random and almost forlorn online search.

“We were looking at the earliest plan of the building (Temple Works) that we’d seen to date,” Lee continues in describing what he found “and although it didn’t give us any more (schematic) information than we already knew – it was basically showing the number of conical lights that were in the main mill – just the very fact that it had gone into such detail at such an early date after the building had been built, just a matter of years, it was quite incredible that he (Fergusson) had used it as a case study.”

(Image source: Popular Science Monthly, vol. 31. -1887 - James Fergusson)

In his study, Fergusson systematically deconstructs Smirke’s proud achievements, but stops short of blaming the famed designer himself. Smirke was exonerated from responsibility on the grounds that he was merely delivering what the trustees had commissioned, whilst also suggesting he was somewhat held to ransom: “The .. museum is as bad and as extravagant a building as could well be designed” Fergusson wrote “but let the blame rest on the right shoulders… …though I have much to say against the buildings, I entirely exonerate the architect. As a servant of the public, he did what he was told to do, and did it well. It is true his work is an entire failure; but, I repeat, let the blame of that rest on the shoulders of those who misdirected him in the performance of his duty. The proposition of the Trustees was simply this – ‘do as we wish, and you shall have £35,000 and a knighthood – if you insist on your own absurd notions, you shall have nothing’.”

Fergusson proposed that the British Museum should be split into three separate entities - Natural History, Antiquities and coins, and a Library - pre-empting what expansion and progress has subsequently made inevitable. But he was coming at it entirely from a practical and architectural viewpoint. Fergusson points to the exorbitant costs and design failures of Smirke’s design and instead suggests an existing building as the perfect model for this and the future development of the museum.

Specifically describing his proposals for a separate British Library, Fergusson wrote: “…in taking a building which has been erected, and whose cost is consequently known, and which would answer nearly for the purposes we are proposing, so that with few obvious alterations it may be adapted to its new destination. Such a building we fortunately have in the great flax-mill erected by Messrs. Marshall at Leeds…”

It reads like Fergusson is proposing that Temple Mill – as it was then known – be refurbished and adapted to house a new British Library, neatly foreseeing what the current collaborators in Leeds hope to bring to fruition in the coming years, but he is actually proposing Temple Mill’s inherent design features as a suitable model upon which future buildings should be based.

Fergusson breaks down his reasoning in a set of compelling arguments:

- He would not advocate use of the endearing Egyptian frontage as that would add unnecessary cost.

- He states that if he were duplicating the construction he would raise the roof by 10 feet and “as a further security against fire, to substitute brick piers in cement, with a hollow cast-iron coring, for the iron pillars.”

- He recognises that the accommodation of a library “would require a higher style of finish, and some ornament internally…” than currently existed in the Spartan and bleak interior of the building.

- He proposes that replicating Temple Mill’s design would be more fire-proof having virtually no combustible materials.

- Further, due to having “compactness of form and there being so little external wall - besides the unlimited means of openings in the roof – it would be far more easily warmed and ventilated than the present building.”

- He argues that using this model, a library could be much more easily and sufficiently lighted than the present building, and the series of skylights could be made even larger if so desired.

- Finally, he adds that “no single book would be at a greater distance than 250ft from the bar of the reading room” (with ‘bar’ thought to mean a central desk that the library porters would use to collect books) and that the modular construction allows for great expansion. He includes a diagrammatic plan of how this would work with each new “row” across the width providing accommodation for another 150,000 volumes.

(Image source: unknown - the vast interior of Temple Mill)

Having comprehensively argued the case for Temple Mill’s functional and practical design brilliance, Fergusson then adds that it should also be used as the framework design for a museum of natural history and a department of antiquities. These separate entities did indeed happen, but not in the format Fergusson strongly put forward.

Fergusson further agues a case for the ‘National Gallery’ and a new ‘National Record Office’, which to this point hadn’t existed before. For the National Record Office he proposes a building in the centre of the vast courtyard of Smirke’s British Museum, thus anticipating the now famous Reading Room (although not circular).

Again, this is all costed and detailed; and, again of this he states “the mode in which I would construct the interior would be something of the Leeds mill model.” He also provides detailed costings and estimates for further ancillary buildings and castigates the library section of the British Museum for its class-related indexing and proposes Libraries and Art Galleries for every town, all to be constructed on the Leeds Mill model.

In this 92-page diatribe, Fergusson comes across as a sage observer and a fount of all knowledge, and certainly an advocate of the foresight and inventiveness intrinsically woven into the gift that James Marshall, James Combe and Joseph Bonomi combined to bestow on industrial Leeds in 1838, just ten years before Fergusson’s love letter to its efficient, operational and resourceful brilliance.

“He was an historian” Stephen Levrant, principal architect and founder of SLHA, says of Fergusson “and the whole tone of the pamphlet that Lee found was all about self-promotion, and a lot of architects did that at the time. But Fergusson did make a name for himself at that, because he was really pushing himself forward and using what were then quite novel techniques for publicity, that’s really what it was. The idea that pushing something out that was a bit controversial, and a bit salacious in a way, was all good stuff and that’s what you wanted to do to get people to notice you and what you were saying. But on the other hand, the downside was that there was no way from writing that pamphlet that he was ever going to get a job out of it!”

Stephen outlines the undeniable foresight that Fergusson possessed though, not just in matching Temple Mill with the British Library, but in understanding the brilliance and importance of Temple Mill’s design, “It’s very, very interesting that somebody with their finger on the pulse of architecture at the time, decided that this (proposing Temple Mill as a model for a British Library) was a revolutionary idea and should be put forward, although of course it all fell on deaf ears. But the interest really is that someone of his stature took the trouble to write that document, all based around what Marshall had done. And that in itself was very unusual.”

“That obviously shows it was a building that was being talked about at the time,” Lee adds “and it was known in those circles to be an example to look at, so it shows how unusual it was.”

Fergusson’s vision and his ability to grasp the concept of Temple Mill and interpret it in a practical fashion is matched by his prophetic imagination in how he saw culture and civilisation evolving, namely the introduction of public libraries available to everyone, regardless of their standing in society, and the importance ascribed to them.

Stephen continues: “He was saying ‘let’s have this idea of outreach stations and public libraries’, which again was quite a revolutionary idea. Knowledge was being disseminated at that time, in various forms, and literacy was gradually gaining ground, so he’s using all those tools to say ‘look we can do this, we can disseminate knowledge, we can have these municipal museums and art galleries’, but you’ve got to remember there was nothing like this at the time, you couldn’t go into your local public library and borrow a book. It just didn’t happen. If you had circulating libraries, which were in their infancy, you had to pay, there was no public philanthropy to do that, not until much, much later. So his ideas were quite revolutionary, and I guess too controversial for people to take seriously.”

In dissecting the idea of Temple Mill the way he did, Fergusson insightfully mimicked the thinking of its creators and designers and fully understood the innovative way the building offered much more than first appeared.

“His (Fergusson’s) whole approach to this was the use of a modular system, and again, that’s a hundred-or-so years before anyone was really thinking about modular construction systems in that way. Of course now it’s the way you build, everyone uses modular grids. The mill buildings, the more vertical ones, they did have grids and they did have a system, but Marshall’s was much more comprehensive and it was something that was designed to expand, that was the point and Fergusson really emphasised and exploited that.”

Clearly Fergusson was a cheerleading advocate of ‘the Leeds Mill’ based on its fundamental concept, which, pointedly, was strong enough to form such theories based on diagrams alone, given neither Lee nor Stephen believe Fergusson will have actually visited the Mill or met with Marshall to discuss his conception. Such unwavering beliefs were formed from its unique design seen on paper only.

“It was hugely known and illustrated,” Stephen says of Temple Mill as soon as it was built “and references to it pop up all over the place, because it was so revolutionary. There was this whole idea that, in everybody’s mind at this time in the 1840s and beyond, a mill was a vertical building, floors stacked up, that’s how mills worked. You had one floor on top of another, to get the light in to keep the machinery going. And the idea that you would suddenly take it apart and spread it over a large area was something that must have been hugely difficult for people to even comprehend at the time.”

(Image source: Flickr/jcw1967 - used with permission - the unmistakeable facade of 'the Leeds mill')

Leaping back to the future, Stephen continues “It’s precisely for those reasons, because it’s so unusual, that we’ve all got these concerns about the structure and the construction. And we come across this quite often in our work, where you have a building which has, by today’s standards, inherent defects; and we’ve always said right from the start: this is a ‘bumblebee’ of a building, it just shouldn’t stand up. It collapsed four times during the construction and sadly, three people were killed. They just kept finding other ways around structural problems and this is why it’s such a fascinating building.”

Alas, Fergusson finishes the section of his pamphlet lauding Temple Mill’s design and its suitability for hosting a British Library, by stating: “All this is, however, speculating on what might have been, but is now impossible.”

But of course, no love is impossible. When Fergusson wrote this case study in 1848, it appeared that the conscious coupling of the two institutions was an opportunity missed, and a big one. But nothing is forever, and whether the possible, eventual partnering of Temple Works with the British Library is a serendipitous coming together, or a second chance after a near-miss nearly two centuries ago, is open to interpretation. But one thing about the current plans is certain.

“I think it’s a major opportunity,” Stephen enthuses “because it ticks a lot of boxes. But it’s still a big mountain to climb. And the interesting thing from a historic building point of view, is that you’ve got recognition from the British Library that here is actually a major heritage asset that is Grade l listed, like the British Museum, so it’s got that level of importance. Rather than saying ‘oh we’re just going to build a big modern box somewhere, and dress it up a bit’, they realised the building itself has huge social, cultural and economic value to the area, and to Leeds itself. So in putting those things together, what they’re doing actually is immensely encouraging in the way that the cultural life of Britain should be going on; the dissemination of information, which is the age we’re in. And while there’s a lot of people saying ‘well you don’t need buildings anymore, we’re all at home working and buzzing away at our computers’, the British Library have gone beyond that and said ‘well actually you do. You do need places where people meet, you can still touch and see things and objects you cannot possibly do by remote means’. So all that is tremendously exciting. And here is a building that was designed for one particular purpose, but actually that purpose, at the bottom of it, was flexibility. What Marshall wanted was a flexible space. And that, again, was incredibly far-thinking of him.”

Lee also sees the collaboration that the British Library, CEG and the Council are working on as an unforeseen opportunity and an accidental quirk that is being capitalised upon: “It’s incredible that we’re talking about the British Library now and they were talking about it over 150 years ago. It’s just an incredible coincidence. And we’re looking for the same things, we’re looking for top lights and how do we divide the space?”

The British Library, CEG and Leeds City Council have the motivation and resolve to try to finally realise James Fergusson’s vision, and to offer the best chance that these natural bedfellows can finally find a home together. Because every kind of union is a journey of sorts.

“The building itself is amazing,” Stephen concludes “this idea of a use for it is an incredible opportunity really. It will be unique in the country, I think. There may have been examples before where people have tried this, but it’s a remarkable combination and everybody’s working very, very hard to make it happen. There are a lot of problems to overcome, but what the British Library are saying is that ‘yes, we think we could use this’. And in fact, how the brief is evolving is that they are adapting, they are saying that they need various spaces for various functions, and the architects and ourselves are saying ‘well the building will give you spaces and areas that may have a different configuration and limits’ and they’re saying ‘we’ll adapt the brief to a degree instead’. So that is the kind of textbook way you should be re-using a historic building; allowing the building to lead in the design.”

Many of us may have shared a similar convoluted, painstaking and emotionally-draining path to eternal contentment; a brief encounter on a train perhaps, where paths cross and a nervous, furtive glance is shared, but no words are spoken and years are spent asking distant, agonising questions about how that person sounded, what they were called and how it could have felt. And, just like that, 172 years later, we drop something in a queue at the Post Office and someone behind us bends down to pick it up; our eyes meet again and it feels like the right place and the right time. It’s happened to us all, right? It might seem fortuitous, but all roads point somewhere and eventually we just find the way.

We hope that now can be the right time for Temple Works and the British Library to join forces and, if not ride off into the sunset together, build solid grounds for a fruitful and beneficial future which protects the heritage and culture of the country and bequeaths a suitable gift to the city of Leeds. And most of all, offers a future to one of our most cherished buildings, which, let’s face it, has been in need of a little love for quite some time.

(Lead image - image credit: British Library - used with permission - the storage void of the British Library National Newspaper Building at Boston Spa)

.jpg&w=500&h=300)