Untitled But No Longer Unseen – how CEG and Leeds Arts University are bringing Harry Thubron’s forgotten mosaic back to life

June 28, 2021

The definition of public art, according to the Tate institution, is “art that is in the public realm, regardless of whether it is situated on public or private property”. In that sense, Harry Thubron’s 1964 mosaic hidden away on a wall in the car park of a dilapidated former warehouse in Holbeck, Leeds, is still very much public art, and the fact that it is unseen, unsung, and perhaps unloved, only adds to its interest and intrigue. But any doubts that may have persisted about whether this was public art can now be comprehensively dismissed, because CEG and Leeds Arts University are about to rescue it from disrepair and probable demise, and restore it ready for suitable reverence.

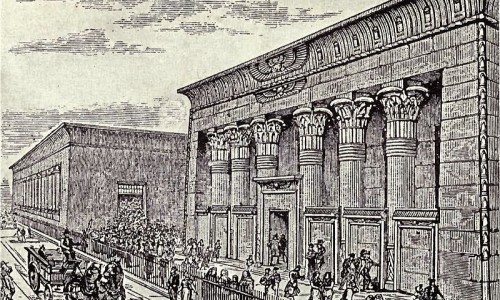

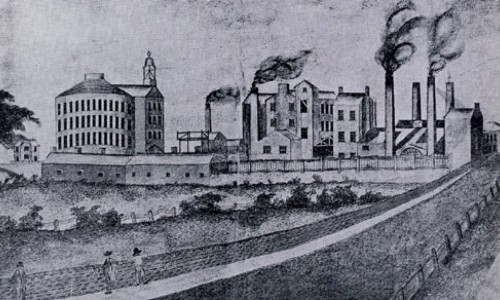

Something about Holbeck attracts a clashing of cultures and conventions, where unlikely partnerships are formed and incongruous statements are made. Around the corner from an Egyptian temple built when the industrial revolution was at its choking, fume-filled heights, is an intricate tiled mosaic created by a radical and pioneering artist in the free-form heyday of the 1960s.

And not enough people know that. Indeed, you might have walked past this unique slab of post-modern virtuosity a hundred times without realising it was there. But times have changed in Holbeck; the Temple district has stimulated excitement in this area of the city, there is vibrancy and energy and animation in these streets, and so too Harry Thubron’s untitled monochrome mosaic needs a similar injection of purpose and effervescence. So it is being removed, refurbished and re-located, to offer it a prominent stage and one which takes its unlikely story full circle.

Harry Thubron was an innovative artist and lecturer born in Bishop Auckland in the North East of England in 1915. His work combined modernism with abstract forms, not only in painting, but using wood, metal or resin to create collages and assemblages with materials found which usually had an industrial connection.

However, Thubron became best known as a provocative art teacher and lecturer. He worked in Leeds between 1955 and 1964 during which time he was made Head of Fine Art at Leeds College of Art, installed as principal mainly to instigate change. He had grown frustrated by the conformist and restrictive methods used to teach art, and radicalised the art teaching process by developing methods that were widely adopted across art education in England. Indeed, Leeds became an unlikely catalyst for change and a centre for innovation in art teaching in the UK.

Thubron established the Basic Design Course, a programme inspired by the German Bauhaus college. In this programme, art and design students were not taught specific skills for any of the disciplines of art and design, but visual literacy in the use of colour, establishment of form and construction of space. He advocated art that was spontaneous, exploratory, proactive and about self-discovery, rather than art that simply copied or followed traditional methods.

In developing the course, Thubron formed close links with the School of Fine Art at the University of Leeds and also was credited with creating the prototype which led to the forming of polytechnics. He sent students to work on collaborative projects with engineering students at the Leeds College of Technology, and out of this partnership, Leeds Polytechnic was formed.

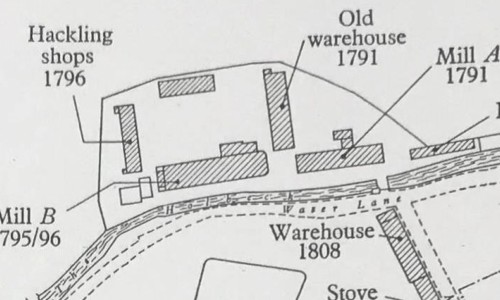

In his final year in Leeds, 1964, Thubron was commissioned to produce a mosaic by a company called Gillinsons & Dewhirsts, two separate businesses who had merged a few years previously – Dewhirsts once had a general manager called Tom Spencer, who, back in the 1890s, went into partnership with a market trader named Marks, and well, we know the rest - and ran a clothing and drapery business in single-storey premises on Sweet Street West, around the corner from Temple Works in Holbeck.

By this time, Thubron was concentrating on thegeometric relationships between circles and squares in his work. He completed two public commissions in Leeds between 1963 and 1964, one for Branch College of Science, Leeds, a work completed with students and sponsored by Shell Chemicals as a research piece, and then the mosaic for Gillinsons & Dewhirsts.

(An archive video, sadly with no sound, of the unveiling of Thubron's mosaic before several invited dignitaries at Gillinsons & Dewhirsts in 1964)

It is not known why Thubron was commissioned by a clothing and drapery business, but a romantic theory is that Gillinsons & Dewhirsts recognised the unique standing of the area, and in particular the lavish architectural structure that James Marshall created around the corner, and wanted to make an artistic statement of their own, maybe recognising the potential cultural imprint the area could have on the city of Leeds, long before anyone else?

Their premises were once a linen factory and a rival to Marshall’s business known as Charles Fox & Sons, and indeed Gillinsons & Dewhirsts were continuing the fine tradition of clothing manufacture in the area, and which James Rhodes & Co Ltd maintained in Temple Works itself before passing the building on to Samuel Driver and then Kays. Maybe Thubron’s well-known use of industrial materials in his art forms also singled him out as the most appropriate artist to bestow the area with his work?

Thubron’s commission was left untitled, and consisted of sections of 20mm vitreous glass tesserae. The small tiles were mounted on paper sheets in Thubron’s studio and then installed in render and face-grouted on the wall at Gillinsons & Dewhirsts warehouse at Sweet Street. The mosaic measured 4410mm x 6180mm overall and has remained in situ ever since.

Although Thubron went on to lecture in Lancaster, Leicester and London, he had a public exhibition of his work back in Leeds at the Queen’s Square Gallery in 1967 and later also showed at the Serpentine in London. He settled in London but had working excursions to the south of Spain and Jamaica, received the OBE for services to arts education in 1978, but died at home in Lewisham in 1985. His work is still displayed at the Tate Britain, Leeds City Art Gallery, the Leeds University Gallery and the Museum of Hartlepool, near where he was born.

But the untitled mosaic in Holbeck is perhaps his most fascinating, and yet undervalued legacy. It has stood in the same place for 57 years, visible to the passing public beyond locked gates but in some ways invisible as its materials have aged and failed. Gillinsons & Dewhirsts are known to have operated into the 1980s, and the buildings were used as a storage facility since then, but have been derelict and empty now for some time. With CEG’s exciting news, bringing Drapers Yard back into productive use- the adjacent former ‘1953 Building’ used by Kays Catalogue - the dilapidated Gillinsons & Dewhirsts buildings behind it are to be demolished, and the mosaic itself benefits from no statutory protection. However, a commitment has been made by CEG - working in partnership with Leeds Arts University and starting at the end of June 2021 - to salvage Thubron’s mosaic and carefully reposition it in a location which reflects its provenance.

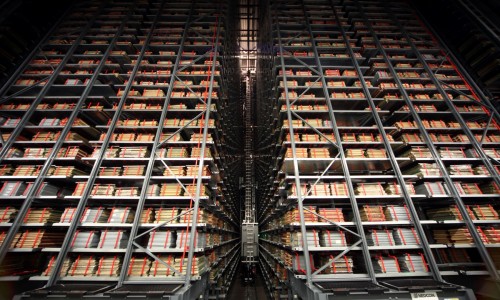

The Leeds College of Art was founded in 1846, and in 2017 it was awarded university status and renamed as the Leeds Arts University. It would be nice to think Thubron’s development of the polytechnic concept in the 1960s created a pathway for such progressive thinking in how education is structured, but what is definitely fitting is that CEG is working with the Leeds Arts University to safely remove and store Thubron’s Sweet Street West mosaic, with a view to restoring and re-siting the piece in the future for public display on the University’s Blenheim Walk Campus. The University has previously undertaken a similar project to restore and display the Eric Taylor Mosaics that were removed from the Merrion Centre in Leeds and are displayed outside the Blenheim Walk building. Not only does this retain another important piece of art, it gives it a more public setting allowing it to be appreciated as a bequeath to the city of Leeds, and perhaps most importantly, it will sit proudly in the grounds of an establishment in which Thubron installed so much profound change.

David Hodgson, head of strategic development at CEG said: “It is fantastic that we’ve found a solution to save and commemorate this important piece of art. A specialist company will work alongside the Leeds Arts University to rescue Thubron’s mosaic. Together their skilled teams will carefully remove and restore the deterioration it has experienced over nearly 60 years, preserving this valuable piece of art and culture for the city.”

A study by the Mosaic Restoration Company – commissioned by the university to relocate the artwork - has concluded that the mosaic can be safely removed from its current fixing, cleaned and restored and re-mounted at the university. The removal process alone will take two weeks, and it is thought the reconstruction process could take up to four months.

(Photo credit: Mosaic Restoration Company - Damage to the glass mosaic tiles after 57 years of exposure)

After being exposed to the savage climate of Holbeck for the last 57 years, not surprisingly the mosaic shows many signs of aging, to the extent that its presence fades into the ramshackle old industrial buildings. There are missing tiles, cracks and fissures and areas of ingrained dirt. Some of the top five rows of tiles were poorly installed back in 1964 and other tiles have been de-laminated. There are areas of asbestos around the outside edges of the mosaic and the background rendering used materials which have grown brittle. Newer materials use modern additives which allow for movement and expansion.

The key decisions that will need to be made are whether to retain the deterioration in some areas as it stands – accepting blemishes as adding charm and character - or to sympathetically restore the piece. A colour-match survey has already determined a close enough match for the missing or damaged tiles, which are mainly black and white but also have areas containing various tones of coloured glass tiles.

(Photo credit: Mosaic Restoration Company - colour matching tiles for the restoration)

Fortunately the mosaic was constructed in small sections of 315mm by 630mm, so each slab section can be carefully removed, its condition recorded and the section cleaned and stored in a way that allows the mosaic to be faithfully reconstructed. This will be done on a wire mesh frame, but the exact location and method of final mounting has yet to be agreed.

Professor Simone Wonnacott, Vice-Chancellor, Leeds Arts University said “We are really pleased to have worked with CEG to save an important art work. Harry Thubron was an inspiring teacher and his work developing what was then called the Basic Design course has been hugely influential in the teaching of creative subjects nationally and internationally.”

In some ways, retaining the deterioration in the mosaic feels somehow appropriate, if that is the choice that is made, given Thubron’s approach to art and the harsh environment in which the work has been displayed. It won’t have been by design, but the mosaic being hidden away in a disused warehouse car park in recent years tells a story in itself. Relocating it in its maker’s successor home at Leeds Arts University completes the story perfectly, but perhaps the work should be able to explain its own journey in its cracks and dirt and weathered exterior?

(Photo credit: Mosaic Restoration Company - the delicate removal process begins at Sweet Street West)

Martin Hamilton Leeds Civic Trust Director said “Thubron’s mural deserves to be better known, not only as one of his best pieces of work but also for what it represents as a piece of industrially-commissioned art. By relocating it to Leeds Arts University, following a sympathetic restoration, we hope that more people will learn about the contribution this man made to the story of art in Leeds.”

Certainly this is a gift to Leeds which should be celebrated, and although Thubron’s maverick methods only resided in Leeds for a short time, his renegade approach is perfectly in keeping with the city’s wider vision of being bold, and being singular and being confident with it. CEG’s vision for Temple is re-imagining a former industrial heartland but doing it in a way that retains its character and unashamedly promotes the toil, the ideas and the radical thinking that came before. CEG are weaving culture into unlikely surroundings, bringing Light Night Leeds to Temple, along with artwork to Chow Down at Temple Arches and exciting community-based partnerships with Slung Low and the British Library.

In gifting Thubron’s mosaic as a re-location close to its originator, perhaps CEG are doing the same thing, but in a very different way. And that strikes me as something Thubron himself would wholeheartedly agree with.

.jpg&w=500&h=300)